This story was originally published in print — one of our most cherished interviews, capturing Tracee Ellis Ross in her fullest form: wise, whimsical, and wholly herself. Until now, you had to hold it in your hands to feel it.

We're bringing it online for the first time. If it resonates, support the work: buy the Beauty Bible and subscribe to our Substack. That's how we keep going.

Tracee Ellis Ross was the first Black woman I saw on-screen who reminded me of the women who raised me: curious, independent and blessed with whimsy. Both my mother and grandmother — two of the most self-assured women I know — could be found randomly breaking into a chorus of show tunes or contorting their faces to deliver a joke. They laughed loudly and left men who didn’t serve them; their beauty didn’t begin and end with their appearance. I remember stiffening at their audaciousness as a self-conscious preteen. Gritting my teeth to say, “Mawwwm stooooop,” as she mindlessly enjoyed herself standing in line at Macy's. I had no idea she was gifting me a blueprint I would need later.

I was fourteen years old when MTV debuted a new sketch comedy series called Lyricist Lounge Show. The show, which only lasted a season, featured a slew of musical guests such as Erykah Badu, Yasiin Bey (then Mos Def) and a fresh-faced, twenty-eight-year-old Tracee Ellis Ross. Back then, I had chosen drama as my high school major, and my inherited silliness felt misplaced among my friends. So, in the first episode, when Tracee played a woman who used beef jerky to scrub her feet in a mock commercial, I thought she was brilliant.

Someone informed the room that the woman on-screen was “Diana’s daughter,” forging my first understanding of duality. I didn’t know you could be the glamorous daughter of a Motown legend and be farcical and playful. A few months later, when UPN revealed their fall 2000 lineup, there she was again, cast alongside Persia White, Jill Marie Jones and Golden Brooks in a new show called Girlfriends — more on Joan Clayton later. That summer, I, like every other Black girl alive, began a decades-long friendship-in-our-heads with Tracee.

With twenty-eight years of film and television under her belt, plus a dozen awards, and a legendary bloodline, the most impressive thing about Tracee is how human she is. It’s this notion of her approachability that settles my pre-interview jitters before Tracee joins our Zoom call. When she appears, smiling and backlit by her notorious indigo wall, I suddenly feel like I’m catching up with a friend.

In 2017, she was named Glamour’s Woman of the Year, and her acceptance speech exemplified the line Tracee walks between immense poise and larky relatability. Forty-five-year-old Tracee stood on the stage for five minutes, expressing how proud she was of her accomplishments despite society’s limited views on what success looks like for women. Tracee victoriously proclaimed that her life was her own. It was the kind of speech only she could deliver, graciously reminding the world that she won a historical Golden Globe but also noting, without missing a beat, she was missing an earring because it messed with the mic, and she “didn’t want to lose the look.”

As we chat, Tracee describes her acclaimed “my life is mine” speech as a benchmark she checks in with on occasion and, most recently, on her fiftieth birthday, which passed weeks before our chat. “The most fun part of turning fifty is realizing that I have actually gotten comfortable in my skin,” says Tracee. “I actually do have an unbreakable, unshakeable foundation for my life. I do know who I am. I intuitively know how to handle situations that used to baffle me. I can be comfortable even when I'm uncomfortable.”

Tracee says self-awareness is something she discovered, like many of us, when she stopped relaxing her hair. “I was out of the home and didn't have my mom to touch up my hair or even take me to the salon on Saturday.” In the eighth grade, Tracee attended school in Switzerland and found herself separated from the caring hands of her mother, who, until that point, was her closest hair ally. “All I knew how to do was just keep blow-drying my hair. So that was a really pivotal moment in terms of the realization that I didn't know how to care for my hair.” Tracee says when she returned home in the tenth grade, she never went back to relaxers, and so began the long, tedious process of transition. “I started to gain a relationship with my hair as it authentically grew out of my head and its texture, and learned what worked and what didn't work.”

It’s an infinitely personal matter, a Black woman’s hair story — which is never just about hair — and Tracee’s is no exception. “I could probably chronicle my journey of self-acceptance through my journey with my hair,” she asserts. Tracee’s early years became the building blocks that not only defined her as a person but inspired beloved projects, including the launch of her haircare company, Pattern Beauty. Unlike the scads of flash-in-the-pan, celebrity-endorsed beauty products, Pattern’s conception didn’t happen overnight. “I wrote my first haircare brand pitch when I first left Girlfriends, so I was trying to get the company off the ground from 2008 to 2019,” remembers Tracee, who says she was simply creating something she couldn’t find anywhere else.

The objective of Pattern Beauty, according to Tracee, is twofold: to meet the needs of the natural hair community and to celebrate Black beauty by making high-quality products that don’t beat textured hair into submission. “There were no products out there that actually matched the needs of my hair, that were designed to not only nourish and hydrate my hair but also [were made] so that I could wear it in its natural texture.” During the conception of Pattern, Tracee insisted on starting from scratch. “I had no interest in slapping my name on the formulas that existed, so I went through about seventy-five samples to get to the first four SKUs, and then we pushed our launch because I couldn't get the leave-in conditioner where I wanted it to be.”

“I've been a shopper my whole life,” she continues, “I feel the most compelled to shop when I feel good, not when I feel bad. I wanted a company that was designed and marketed to the customer as a form of celebration and joy, and meeting you where you are.”

I can attest that the care and intention put into Pattern are mirrored in the brand’s offerings. The first time I bought the twenty-nine-ounce container of the Heavy Conditioner, I felt years of trauma melt away. Instead of praying in the shower for more than “a dime size” of product made and packaged for white women, I could unabashedly pop the top off and scoop out a handful worthy of my strands. Only a woman who has been othered by a bottle of conditioner can identify usability as a central consumer need.

This is what Black women do. Self-reliance is a consistent theme among Black founders in the beauty industry. But Tracee wants the industries vying to serve us to wake up and pay attention. “I was the person who pushed for McKinsey to do the report on Black beauty,” she recalls, referring to the 2022 quarterly report, Black Representation in the Beauty Industry. “There's just not enough information, and we shop differently. We have a different hair cycle for washing. We're not listened to.” Tracee goes on to say that she thinks about how young people interpret the narratives around Black hair, especially those who are teased and bullied because of it. “They don’t see the beauty in their authentic beauty, the power of their texture and the way it tethers them to their stunning history; both the good and the bad of that history.”

Tracee’s desire to shift beauty narratives is echoed in her six-part docuseries Hair Tales, streaming on Hulu. Ross, along with Michaela angela Davis and Oprah Winfrey, executive produced and curated a series of conversations about the intersectionality and historical context of hair and Black women. She notes, “It dovetails perfectly into my life’s mission to join the chorus of people that are helping to make our world a safer and more just place so that we can all be free to be ourselves.”

Black women are often removed from the mainstream hair conversation, and the consensus is that our version of beauty is not quite right. “Often our story as Black women and Black people, in general, is decontextualized in this country,” remarks Ross, “but specifically as Black women, we are siloed off, and our narrative doesn't string together with everybody else's. We really wanted, to the best of our ability, to put together a beautiful collection of stories and use hair as an organizing principle, to share our humanity.”

Removed though we are from market research and product development, we find kinship through our shared experiences. “We almost all have a scissor story,” says Tracee on takeaways from Hair Tales, “So many of the same experiences in our culture resulted in shame for us. I don't know that we've had an opportunity on a grand scale to have that kind of connection. I feel there's never a beautiful story about our lives. So often, our story is told through struggle, hardship and difficulty, and that’s a part of the experience of being a Black woman in this country and in this world. But it’s not the only thing.” The series includes a historical dive into our relationship with hair, such as the way white-defined respectability threatened our livelihoods and still does today.

“It's been very important to me to frame it with Girlfriends so that there's no confusion and people don't unconsciously take on Joan and think that is the roadmap to womanhood.”

These dangerous stigmas are ones that Tracee herself inadvertently tackled by appearing on television as a Black professional woman with unaltered natural hair. When I ask Tracee what similarities existed between herself and Joan Clayton, she exclaims, “All of it!” and erupts into laughter.

Tracee admits to being incredibly organized and tactful like Joan and very much a solution-focused person. But there are two glaring differences, and one of them is Joan’s maniacal affinity for the holidays. “I'm a nut for connectedness and being with my friends and family, but I don't decorate, I don't make pfeffernusse. I'm not that person.” The other difference is Joan’s obsession with her relationship status. “The biggest epiphany for me,” says Tracee, “ is that I spent eight years playing a character whose dialogue was all based on being chosen by a man.”

It’s a relief to hear her say this. There is something so specific about growing up as a millennial when Black girls were not yet considered magic, and no one called our hair a crown. Characters like Joan Clayton confirmed a standard at the time, the wife-shaped box we were all encouraged to chase. “That was [Joan’s] underlying goal and mission in every arc of her life,” acknowledges Tracee, “I have spent the last ten years publicly changing the narrative and saying that as a woman, I’m also the chooser. It's been very important to me to frame it with Girlfriends so that there's no confusion and people don't unconsciously take on Joan and think that is the roadmap to womanhood.”

Many of us are deconstructing our ‘90s miseducation, including old lessons about self-love, work, identity and particularly marriage and parenthood that were taught before time pulled back the curtain. “You can have a fulfilling and beautiful life and choose — even if it's not something that you intended — to say I don't want to get married or don't want to have children,” says Tracee. “These are all very valid choices to have a fulfilling and robust and beautiful life that’s worthy.”

On the flip side, as women become less compliant with the patriarchy and more invested in personal growth, there’s been a collective yawn around dating in general. But Tracee, who defiantly proclaimed she would only enter a relationship that enriched her already full life, doesn’t think dating is a waste of time. “It’s just as much about meeting another person as meeting yourself,” she insists, “It's discovering what's important to you, what you care about, how you feel when you walk away from somebody and learning how to do that for yourself.” In her opinion, the most important requirement is to have fun and see it for what it is: human interaction. “You get to get dressed up; you get to go somewhere and basically practice being yourself in proximity with another person.”

Instead of discussing her ideal partner, I ask Tracee who she imagines as her ideal costar, specifically in a romantic comedy. Tracee’s face warms, and her eyes get big and curious. “If we, like, pick an actor? Wouldn’t that be fun? It wouldn’t be Idris Elba,” she reasons (sorry, Idris). “Would it be Jonathan Majors in ten years?” I suggest we toss age right out the window and focus on vibes. “Ooooh,” Tracee hums, “He was in Bullet Train . . . Brian Tyree Henry.” Collective agreement ensues; it just makes sense. Tracee’s opposite would have to be someone who is comfortable in their own skin, full of character and humor and effortlessly loveable. “I think we should pose it to the public,” says Tracee in a just-kidding-but-totally-serious tone.

Another strong parallel between Tracee and Joan is the intention of having friends who feel like family. Although Ross admits that much of the drama we watched Joan, Maya, Lynn and Toni go through on the show was for entertainment, the “thick and thin” part was as real as it gets. Tracee credits her real-life, tight-knit inner circle for helping her understand relationships and for her own personal growth. “I think I’ve learned how to show up through my siblings and my chosen family of friends,” says Tracee, who once relied on her older sister Rhonda to proofread her emails. “I can now do it on my own, but Rhonda used to be my copy editor. I've learned how to be a better person through them,” she continues, “How to be a friend, how to be a sister, how to have uncomfortable conversations. I have learned that it’s safe for me to share my vulnerability, my fear, discomfort and grief. That I’m not alone.”

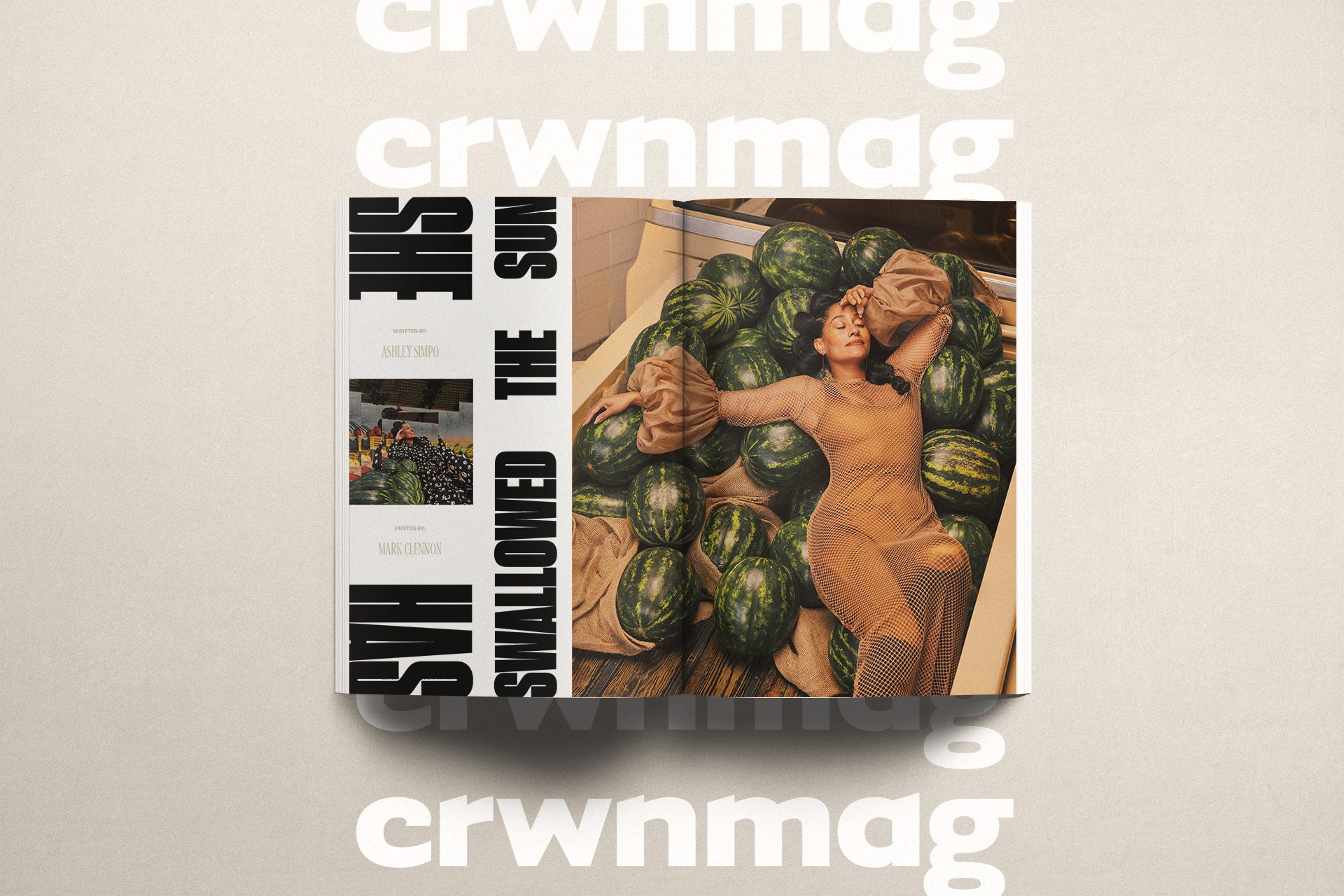

I want to look like I swallowed the sun,” she says excitedly, “My mom looks like she swallowed the sun. I want to look like I'm filled with myself.

When it comes to her family, Tracee undoubtedly has an incredible beauty source from which to draw. She grew up watching her mother prepare for the stage, and Diana famously did her own glam throughout her career. “No one's ever done her hair and makeup,” says Tracee, a look of reflection spreading across her face, “It's still one of my favorite things now to do for myself.”

“When I have hair and makeup done for me, and I get dressed for an event, it's fun-ish. What’s fun for me is when I transform myself. I'm transported back to what I witnessed with my mother, which is what originally helped to define beauty as a tool for agency, a tool for you to transform yourself into superhero versions of you, or a corporate version of you, or a business version of you. It's a tool, and it's an inner experience for you that you get to hold and use as you please.”

Now, at fifty, Tracee says she’s happy to still very much be herself, and possibly even more herself than she’s ever been. She has managed to arrive at this stage uncluttered by the mess of voices that tell women their beauty is determined by their proximity to youth. “I want to look like I swallowed the sun,” she says excitedly, “My mom looks like she swallowed the sun. I want to look like I'm filled with myself.” Tracee inspires us to rebuke the trite definition of beauty that stops short of seeing the entirety of a person, including the contents of their soul, the part that grows deeper and more complex with time. When beauty is defined by one’s connection to and relationship with themselves, it doesn’t require us to miraculously age backward. “I look at images of me in my twenties and thirties, and the way I remember it is different than the way it looks. My memory tells me it was tighter, prettier, younger and thinner. I look back, and I do see a tighter, thinner, younger person, but I don't see as much of me.” Tracee continues, “I look at myself now, and I see me. I see what I feel like on the inside, on the outside.”

This thing that Tracee has found through time — a deep inner acceptance — is why she’s the inspiration behind our beauty issue. Because pretty is what you wear, but beauty is what you know. “I believe that beauty is actually an internal force as opposed to a physical thing,” Tracee declares when I ask about her general philosophy. “My wish and my hope for everyone is that we start to redefine beauty for ourselves more and the language of that.”

Tracee, evolved and in her juiciest era yet, has become her own blueprint and her own source of truth. Her parting words, now scribbled inside my journal, echo the lessons my mother unintentionally taught: “Laugh as much as you can and care for your physical self as a way to put love into action.

“I did a workshop for many years with young girls, and one of the exercises we [did was] introducing [ourselves].” Eye contact, Tracee explains, was often a point of contention for the students. Some even broke into tears from the intensity. “When you soften the gaze you allow it to be a connecting space. It's not from a place of looking to discover what I like or don't like, but just to be present with myself,” she explains. “And then on days I don't feel great I put on some fucking lipstick. A lip will change everything.”

Get one for your coffee table!

The CRWNMAG Beauty Bible isn’t just a magazine — it’s a collectible artifact of our beauty, wisdom, and wellness. Featuring Tracee Ellis Ross and a chorus of voices reimagining what it means to care for ourselves, deeply.

Beautifully written Ashley! Such gems to treasure. 🔥💕